I never heard of that, surprisingly, but deducted that from simple known facts. I hope I'm missing something.

Maybe my idea is just wrong? It's simple enough to explain here:

Elevated CO₂ levels in office air reduce the cognitive ability of office workers, that is well established.

That is measurable by experiment. Complaints about drowsiness start at about 1000 ppm CO₂ in air.

Reduction in cognitive ability does happen with drowsiness, almost by definition.

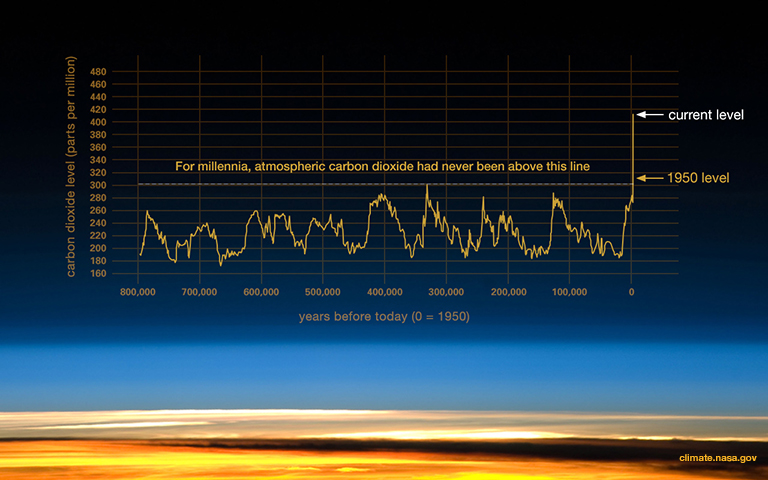

The level of CO₂ is currently a significant fraction of 1000 ppm, about 409 ppm as of November 2019.

The CO₂ level in a typical western indoor working environment raises by multiple 100 ppm over the day, exhaled by people breathing in the working environment.

With an increasing base level, an increasing level in workplace air reaches a fixed threshold sooner, because CO₂ levels are additive.

The base level does increase. Therefore a level of CO₂ that reduce the cognitive ability of humans is reached earlier in a working day.

If the base level is higher, base level plus the additional CO₂ in office air reach a level that reduces cognitive ability sooner during a work day.

This happens globally in many workplaces.

That is true for any values of base concentration, threshold concentration and maximum of increase during a day that are of the same order of magnitude. This estimation is optimistic, because it assumes that the effect has a sudden onset at a level that causes obvious symptoms.

To summarize the central points: Some CO₂ concentration exists that has negative effects. An offset in base air concentration results in an offset in the workplace concentration. That means the detrimental concentration is reached more often. For this to be true, the exact numbers are not even relevant.

Ok, what's wrong with that deduction?

I really hope there is something wrong.

If this is a reason to care about the level of carbon dioxide in common air, it is completely independent of climate change, an alternative motivation to do exactly the same thing. That seems very relevant to me.

After a bit of research I found this article which talk about the 15% drop in cognitive function in office with 1000 ppm (which Michael Walsby bourght up in his answer) and a link to the study from where those data are from.

I went straight at the conclusion of said article and from what I read, it seems to be more about an increase in test score based on environment quality (mostly air quality and mold from what I read) and this make a big difference.

The result could be because of an alarming $\small\mathsf{CO_2}$ level that is corrected with a ventilation improvement, or it could just be because the air is easier to breath so student are less stressed out. From what I see, the study only talk about a link between environment quality and performances at different tests. It does not conclude anything about $\small\mathsf{CO_2}$ level, which means that the article which was talking about the 15% decrease in cognitive ability probably over-interpreted the article.

I haven't done more research but I think your concern is probably a wrong interpretation of some articles doing a wrong interpretation of studies that are too fiew to draw a clear conclusion. It's still an interesting topic though but without more studies it's just speculation from what I see.

Acute Exposure to Low-to-Moderate Carbon Dioxide Levels and Submariner Decision Making (June 2018) reports:

METHODS:

Using a subject-blinded balanced design, 36 submarine-qualified sailors were randomly assigned to receive 1 of 3 $\small\mathsf{CO_2}$ exposure conditions (600, 2500, or 15,000 ppm). After a 45-min atmospheric acclimation period, participants completed an 80-min computer-administered SMS test as a measure of decision making.

RESULTS:

There were no significant differences for any of the nine SMS measures of decision making between the $\small\mathsf{CO_2}$ exposure conditions.

Effects of acute exposures to carbon dioxide on decision making and cognition in astronaut-like subjects NPJ Microgravity. (June 2019) 5: 17, which shares an author with the 2016 study, finds: